Mike Kuchar: Picture Palaces

The Stop Smiling Interview with Mike Kuchar

Friday, December 23, 2005

By Michael Joshua Rowin

Sharing a Bronx childhood immersed in movies, twin brothers Mike and George Kuchar developed during the '50s and '60s into two of the most influential underground filmmakers in America ? while still in their teens and early 20s. Possessed by vivid imagination and ribald taste, the brothers were instrumental in giving rise to intentional camp cinema, and did so well before Jack Smith's Flaming Creatures and Susan Sontag's ?Notes on Camp.? And presaging Warhol, they created a factory of their own ? ?Hollywood in the Bronx? ? by using friends and other co-conspirators for their madcap 8mm deconstructions of melodrama, sci-fi, and horror.

Part of the New American Cinema scene in New York in the 60s, where they discovered like-minded filmmakers in Smith, Ken Jacobs, and Ron Rice, Mike and George ultimately embarked on separate careers. Soon began a period of concurrent creative peaks, with George directing the neurotic classic Hold Me While I'm Naked and Mike unleashing his sci-fi extravaganza, Sins of the Fleshapoids, now available on a new DVD courtesy of FACETS/Other Cinema (review forthcoming from Stop Smiling). Since then, both brothers have continued producing film and video prolifically, and Mike has also delved into illustration and work as a cinematographer.

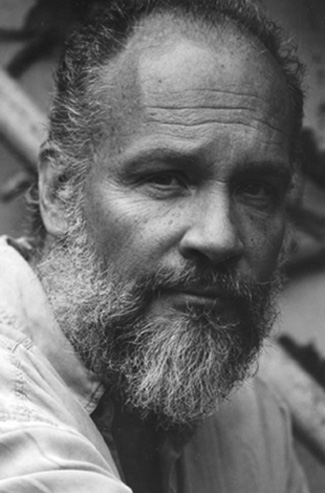

Sitting down for a conversation at the Millennium Film Workshop on the Lower East Side, Mike Kuchar proved as enthusiastic and open as his films.

Stop Smiling: You and your brother started making films at the age of twelve. What images most captivated you as a child and influenced you to make films of your own?

Mike Kuchar: I'm a product of the popular culture that I was born into ? '50s sci-fi movies and biblical epics put out by 20th Century Fox and glamorously garish movie posters and comic books. It was most inspiring to me, that kind of stuff. Movie theaters in the early '50s were temples, they were palaces, they had goldfish ponds in them and chandeliers and always a double feature. I would frequent these places quite often, and on the screen was this other reality, this other world, Mount Olympus, with its own people who sometimes you could see again and again, and they were accompanied by music and nice colors and costumes and plots that were sometimes over the top.

All this was inspiration and got me into movies. I guess when I was looking at the pictures I was analyzing them unconsciously and seeing how they were made and all the gimmicks behind them. These were the images that stayed with me and that I sometimes reflect in my pictures.

SS: You say you were analyzing unconsciously. Could you explain more about that? How do you think those images seeped in?

MK: By watching the cutting, and watching when the main star comes on and turns ? sometimes the music gets louder, it's a repetitive theme that the orchestra plays that somehow seduces you or elevates the person who's on the screen, whose size is huge ? fifty feet! [Laughs] So technically I'm learning pictures by just watching them, the process, the mechanisms of how they're made. When I picked up a camera I began to reflect that or use that vocabulary. It was just an extension of what I was seeing in these movie palaces. So unconsciously, although I often enjoyed the pictures, I was also seeing their fabrications.

There's this thing about camp. What is camp? I guess what the process is, no matter what they're doing, even if they're trying to tell a story that's supposedly really happening, it's all fabricated ? they're actors and there's a camera shooting them, and they might be playing poor people but they're not, they're getting a salary. It's creating an illusion. What I did then was I started to set up my tent on that kind of established form. I'm using it as a recreation ground ? Hollywood, but my pictures are different, they're wrong. The music gets a little too loud, or the makeup ? I'm really conscious of makeup on people ? I tend to go overboard. It's not like defiling or graffiti on a public park, it's more like an interpretation that goes a little off. I'm aware that the thing is artificial, so that becomes evident. But I don't do it to sabotage, it just happens to turn out that way.

It's my job to discover people, make my own stars. Sometimes the way I present them on the screen is the way Hollywood would present their stars, but they're my stars. But I wouldn't find them in Beverly Hills, I'd find them in the Bronx. [Laughs] But I treat them with that kind of technique.

SS: How were you introduced to the underground film scene in New York? Did you feel a proper fit within it, or did you see your attitude toward filmmaking contrasting with the general seriousness of that circle?

MK: Just through a friend, Donna Kerness, who stars in Sins of the Fleshapoids. We went to the same school, we were making 8mm pictures. She said, ?I met this guy [Bob Cowan], older guy, he's a photographer, he's taking pictures of me.? She invited me over to his house. He was Canadian. He stars in Sins of the Fleshapoids. He plays the major robot in it. We went over there, played movies and had fun. We actually made a movie. We brought an 8mm camera and put them in the picture. This was an early 8mm one, a horror picture ?

SS: The Slasher?

MK: Yeah, it's now included in The Slasher. At first it was something else, but eventually we did put it in that. [Cowan] said, ?You know, you have all these pictures you've made. Every month I go meet in a loft downtown at Ken Jacobs's place.? The individuals there were self-motivated, they were painters and sculptors, they started to see if they could express their ideas in motion pictures. It was a get-together of artists. We brought our movies there and they enjoyed our pictures. Ken Jacobs really liked them and he said, ?Look, in two weeks we're going to have a meeting, come again and bring some more pictures.? They got hold of a theater, they wanted to present this new movement, the New American Cinema, so that it would be more like a gallery situation. There was a critic there writing for the Village Voice [Jonas Mekas], he liked our pictures a lot, so he said ?Look, we opened this theater, why don't you have a show. I'll write a good review.? It was called underground. My brother and I never had a problem [with that scene]. When you're making your pictures you can do what you want. Nobody's going to tell you what to do or what you can't do. A lot of the pictures, their topics at that time weren't accepted. It was underground because you had to go to off-off-places, you had to literally go to basements with sofas and fold-out chairs were set up, screens and sheets. We were like nuts. Hollywood was making pictures about crazy people, but here the crazy people were making pictures! [Laughs]

SS: During the making of Corruption of the Damned (1965) you and George began separate filmmaking careers, even as you at times called on each other's assistance and collaboration. Was this because you both recognized you were developing divergent filmmaking styles?

MK: It just sort of happened. I was working on Corruption of the Damned with him because we bought a 16mm camera. And then I wanted to do a color picture ? I don't know why. I think I was listening to electronic music and said, ?Oh, I'll do something sci-fi.? You never can tell what roads you'll start going off on. I was devoting my time to this idea and I just told my brother, ?You take over Corruption of the Damned.? So I was never conscious that we had a different way of making pictures. It just sort of happened that way and stayed that way. What we have in common is that we're interested in making movies, but we don't work on them together. Because he's his own person, he's got his life and inner conflicts that give him plenty of plotlines for his pictures. And I have my feelings. We share equipment, though.

SS: When you were making Sins of the Fleshapoids (1965) were you consciously developing a camp aesthetic in relation to the sci-fi genre, or were you thinking beyond those borders?

MK: I was conscious of, for example, the makeup on the girl ? the eyelashes are just too much. I'm doing it deliberately because I think ?Makeup, makeup, it's a costume picture.? So I deliberately went overboard. But with a fondness ? I like to get lost in this stuff. It was like a celebration of my appreciation of these pictures. And her lover in the film [Julius Middleman] was like those handsome, Hollywood stars like Steve Reeves, those masculine, muscular guys who can't act. Julius couldn't act, he was awful ? he was worse than them! [Laughs] But it doesn't matter, it's just the way it is in those big production pictures. I guess all that pop culture, that junk manifested itself in this picture. I just knew I liked color and costumes. I'd go out shopping and get carried away, anything super-colorful or flashy, I'd just buy it. I couldn't help it, I put it in the picture.

SS: Which particular sci-fi films inspired Sins of the Fleshapoids?

MK: It was a combination of things. Even Hercules pictures when they were first coming out, some of these biblical spectacles. That picture is a complete hodgepodge. I was probably rummaging through a newspaper and there was a picture, Creation of the Humanoids, it was a sci-fi picture. I guess [the sci-fi idea] was in mind the day after I listened to electronic music. I thought, ?What's the plot going to be about?? And then I saw the listing for this movie and I thought, ?I'll do one on robots. My picture will be like this.? Not from knowing the plot of that picture, just from reading the splashy advertisement for it. It was probably like that.

SS: What draws you to the sort of biblical imagery that suffuses Sins of the Fleshapoids?

MK: It's romantic, in some way. It's an escape.

SS: In Fleshapoids there's this flaunting of materials and textures up close to the lens that brings to mind Von Sternberg. Were his films an influence?

MK: More now. But my brother loved his work around that time. And I do now, I really like his work. His films are cinematically voluptuous, the cinematography. I like the plots, too, the eroticism throughout them. Marlene Dietrich is quite a gadget in his pictures. There's also something obsessive in them that's also very interesting. Picture-making is voyeurism.

SS: How did the switch from 8mm to 16mm film and the color stock you were using affect the realization of Fleshapoids?

MK: If you're semi-professional and are thinking about making movies you should not use Kodachrome, which has strong colors in it already. Because if you bring it to a lab what happens is that the colors are only going to become even more saturated. While I was making the picture [with Kodachrome] these heavy-duty camera people, or people who were really into making motion pictures, were saying, ?Whoa, no, the lab is not going to control the color. It's going to get too contrast-y or saturated.? I like what happened. When you make the print the color just hits harder. So when you look at the picture that's what's memorable about it. You're going to see a color picture ? the colors are really there.

When I was working in 16mm I started to become more and more technically conscious, or presentation-conscious. It was a bigger film; it was more of a procedure setting up the camera. Also, when you get older you think more about what you do. The 8mm pictures were all impulsive: ?Do this, go there, this happens, and now fall down.? You go to your spot and you take the shot. It's all kind of subconscious and instantaneous. Later on, it becomes planned. With Sins of the Fleshapoids decorum starts to creep in more. You just refine what it is you're doing ? it becomes more of a conscious process.

SS: I was really impressed by The Secret of Wendel Samson (1966) and how touching that portrait of conflicting sexual feelings and guilt is. What inspired this film?

MK: There was a New American Cinema show at one of these theaters, a mixed program of different filmmakers. After the program ended, we would bump into each other in the lobby. Red Grooms [the versatile pop/mixed-media artist] said, ?I really like your picture, here's my telephone number.? I said, ?I like your picture, too. Maybe in the near future we can work on something together.? It was a start. I wanted to do something fantastical-looking, image-wise, but I had no idea of a plot. So I said, ?Well, I'll make a spider web, hang him in a spider web. Why not, that'll take two hours or something.? So I shot that, but then I started thinking it could be a metaphor. It kind of moved on from that. You see, sometimes I just sort of sit down and start somewhere, you just start writing and thinking and devising situations. I liked the way he look photographically, so I said, ?You have nice orange hair, grow a beard. Let's take up some more of the orange.?

It's strange, he's not at all like [Wendell Samson] in real life, he's like a big silly kid, Red Grooms. Yet in the picture, it's strange, he took on ? he walks like me, and he doesn't in real life. You know, creation, it's a psychic kind of thing, like a medium mystic. You just sort of go along in a trance, because something's trying to express itself. As long as I start somewhere, I'm actually opening a door. It's like talking to a psychiatrist ? you open your subconscious. Things flow out, but it's not an overt, conscious thing. As you get into it more and more, you see how to maybe put the pieces together and come to a solution. But also, with the flashy gun malls at the end, the shooting gallery, I'm thinking that I'm making a movie, too.

SS: You mention on the DVD commentary being inspired by Orson Welles's film version of Kafka's The Trial. Were the psychodrama films of Deren, Brakhage, and Anger, and the way their films work out of sexual preoccupations in dreamlike atmospheres, were those also an influence?

MK: Especially Kenneth Anger, especially the more exotic ones ? Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome. I really admired that picture. The exotic sensuality I found inspiring.

They opened doors and possibilities. It was like a sharing, in a way, seeing other people's pictures. Or else it energizes you. John Waters, the first time I met him at a party, he said Sins of the Fleshapoids kind of energized him to complete Pink Flamingoes. Something that energizes you or gives you inspiration, it gives you impetus to continue what you're doing.

SS: The Craven Sluck (1967), with its trashy send-up of domestic melodrama, seems so ahead of its time from this vantage point (it could easily be a proto-John Waters film). You didn't like this film after it was made and suppressed it from distribution for a number of years. What are your feelings toward it now?

MK: I like the picture, I accept it. It was unfair for me to develop a complex about it. But sometimes that happens. You make your own pictures, and sometimes you have a complete breakdown. Because you put a lot of energy into it and then you're depleted. You're looking at it so many times, and sometimes you become allergic to yourself. You actually become allergic. It's a strange reaction and it can be dangerous. There's only been a very few films that I said, ?Nah.?

SS: What are the other ones?

MK: I've destroyed them.

SS: Really?

MK: Yeah. I take them completely out of circulation. But they were minor, not major things. You see, there's morally ? a film can fail and all, but what it does, it's not contemptible. It's more like a fall. They're like expressions, and when they fail it's bad in that morally you've failed the idea or the concept. The people who watch it would perhaps feel it. That happens very, very rarely.

I also say you can be your film's worst enemy. Because you've seen it so much but you have to work on it in all these stages. When I work on a picture I do the entire thing myself. I do the lighting, the cutting ? you get so involved that there comes a point where you can build a complex. Also, when you finish a picture you're very vulnerable. Sometimes when you invite somebody that maybe you shouldn't invite over to a screening and they say a negative remark, it can be extremely devastating. And unfairly so. What happens is you've opened yourself and given yourself and then something like that can all of a sudden change you because you've gotten to the point where you're getting allergic to yourself, you're beginning to self-hate. With The Craven Sluck it might have been that.

Maybe there's another part of me that's a perfectionist. I was very free-wheeling with The Craven Sluck. I was not meticulous with my set-ups and exposure readings. My perfectionist side said, ?Ugh, I'm too sloppy. Maybe this picture's too off the wall.? Eventually I think that wound up being a plus for that picture! [Laughs].

SS: Do you ever incorporate accidents or chance events into your films? I was particularly struck by the use of dubbed voices in The Secret of Wendel Samson and how the obviousness of that actually contributes to the hallucinatory feel of the film.

MK: I'm glad, yeah. If you feel for what you're doing, it eventually will come out, no matter what your obstacles are. Eventually the film will contain a certain soul or feeling. If that's what the motivation is, though you're not overtly aware at the beginning, it eventually will be incorporated.

As for accidents ? sometimes they're accidents that were meant to happen. You're given signs. They were meant to happen because it turns out better. I find this more and more as I make pictures ? it's a medium mystic. The inner has to come out and be manifest in physical form. So you have to use all kinds of medium mystic powers in dealing with the internal and external world. You have to create or materialize it into a form that's in this dimension, on film. You're going into a realm that's psychic. If your emotions are strong toward materializing this project, most likely things will fall together. In the editing process, people who know nothing about editing, if they happen to stumble in and watch over my shoulder, they might say something correct. They were like guardian angels, in a way. Somehow they were in on it.

Sometimes I desperately wanted, needed to make a certain type of picture, and then I meet somebody and they're the one who makes the picture possible because they had certain qualities, or they would do a certain thing that this picture needed, that you couldn't get from other people. It's lined up, you're given these go-ahead signs.

With movie cameras you can hear when they stop, but with video cameras, you can't hear them. Often I forget to turn them off after a shot. The expressions of people while they're waiting, in between takes, they're truthful expressions that they couldn't otherwise give. And you can use that.

SS: What projects are you currently working on?

MK: It depends on what influences me. A lot of writing for a while. A lot of teleplays, like Purgatory Junction. I did a whole series of teleplays, which got me into writing ? I wanted to see if I could express myself. Because with video you have instant sync sound. I wanted to see if I could get into writing. When I was watching movies or television, if there was a certain writer, like Ray Bradbury, I was very conscious of it because they had a style. I like that with a dialogue picture, when you're conscious of the writing style. I don't want people to talk like they talk on the subway. [Laughs] I want to hear dialogue, but constructed and formed, to express something. I don't want to hear, ?Uh, uh, uh,? or ?fuck,? or ?shit.? I want to hear words composed. Like when I open a book I want to hear the structure of the prose, the craft. So I wrote a lot of teleplays, on video, twelve or so or more.

Then I got to the point where I said everything I needed to say, there was nothing else worth saying, I didn't want to hear myself anymore. [Laughs] Sometimes somebody expresses interest in being in my pictures and I say, ?Do you have any poems or monologues or anything you never got to do? Give them to me, I'd like to construct a picture because I get a feeling from them.? And then visually it'll get me behind a camera again and that'll be the foundation around which I can build a picture. I did a bunch of these. Sometimes they're youngsters. They have writings as they go through their angst period, they write these poems. I become friends with them and say, ?Oh, you should give them to me,? and then sometimes they're in it, or sometimes I'll assign it to someone else. But it's like a foundation on which then my own sensibilities get interjected, both visually and in how I construct the situation.

SS: What do you look for in a performer?

MK: A potential. ?Oh, they'd be good for a story because they have certain flair about them.? Or else you have a feeling about them, it's romantic and you can't do anything about it except make a picture. [Laughs] In some way it should be an expression of love or desire. You hold their image but you put it in a context. When you're working this way there are many, many reasons why you make a picture. They're all motivated by overt and subconscious desire. [The performers] may not be aware of it ? maybe they are after they see the picture! [Laughs].