The Day the Bronx Invaded Earth: The Life and Cinema of the Brothers Kuchar

Forget all those other boring indie brother teams – these guys were the original geniuses of cinema’s bargain basement.

The sudden death, disappearance, or withdrawal of a key actor during the shooting of a big Hollywood movie is the kind of Industry debacle that drives producers into a panic, capsizes multi-million dollar productions, and sends studio flunkies scrambling for damage control with press and investors alike.

Low-budget Hollywood directors working away from the glare of publicity are often able – and forced – to come up with cheap solutions to keep their productions going. Bela Lugosi died in 1956 during initial shooting of Ed Wood’s trash classic Plan Nine from Outer Space, and Wood merely grabbed a chiropractor friend to finish Lugosi’s role with his face hidden in a cape. New York City independent filmmaker Amos Poe lost his male lead, John Lurie, well into the filming of Subway Riders (1981). Lurie simply disappeared. Poe himself stepped into the lead role of the saxophone-playing serial killer, even though he looked nothing like Lurie. Since he also couldn’t play the saxophone, he just held it.

Underground filmmaker George Kuchar goes one step further when confronted with the loss of a key actor: he writes the event into the film and actually finds it inspiring. Instead of substituting a cape-draped face a la Wood, he substituted his own naked buttocks when the Puerto Rican lead actress refused to do a nude scene in his 1962 film Night of the Bomb.

It would not be the last time an actress refused to shoot a provocative scene for George, but no roadblock erected by feminine modesty could impede the steamrolling progress of one of his scripts once a downhill momentum had been gained and the brakes had been greased by reams of florid dialogue. No setback was insurmountable.

In fact, setbacks could be turned into successes, as George went about the black magic of low-budget filmmaking. In his 1987 film Summer of No Return, George had to make the beautiful lead actress disappear, as he remembers, “because she didn’t trust me – she thought I made dirty movies. She thought I was trying to get too much flesh from her. So we had her character burned in a fire and put in a hospital, and that advanced the plot because now we knew that her beautiful young suitor was to struggle to become a plastic surgeon and fix up her from now on bandage-draped face. He had to get money so he delved into the underworld, became a hustler and a drug addict and then had to clean up his act – all to get money so he could train as a plastic surgeon to rebuild her face. So, thanks to her, the plot advanced considerably.”

In George’s best-known film, Hold Me While I’m Naked, the lead actress caught pneumonia after spending hours in a drafty shower, and left. The scene was filmed and written into the movie to help add drama and direction.

No art form demands as much spontaneous, imaginative improvisation as low-budget filmmaking, and no American low-budget filmmakers are as imaginative as George Kuchar and his twin brother Mike. Major figures in the American Underground film movement of the ’sixties, they are the acknowledged pioneers of the camp/pop aesthetic that would influence practically all who came after them, from Warhol and Waters to Vadim and Lynch. That influence is still being felt.

Born in Manhattan in 1942, the brothers moved to the Bronx at an early age. There the tenement blocks, TV-antenna-studded rooftops, bleak blue winters, and littered streets of New York City’s northernmost borough would become their familiar world. A world that they, like most adolescents, wanted to escape. Failing that, they would remake it, colorize it, drape it in cheap tinsel and leopard skins.

The nearby Bronx Park and the Bronx Botanical Gardens offered temporary refuge from the hostile city streets. George would take long, solitary walks in the wilder, more remote areas of the park, to discover idyllic waterfalls and fast-running streams splashing over rocks.

Young George was also keen on violent storms. “Since I was born in a city and lived in a city, New York, all my life, I worshipped nature and storms – anything that disrupted the city in a ‘nature way’.” Tornados were a particular fascination that would figure literally and metaphorically in his cinema. (George’s 1961 film A Town Called Tempest has a remarkable sequence of a tornado destroying a town.) “I think in the ’50s a big tornado had gone through Worcester, Massachusetts, and there was talk about it in New York. It was in the news and for some reason it excited me. The great storm smashing up towns and blowing into people’s lives, changing them.”

Other, less naturalistic forms of destruction were then taking place in the Bronx as whole tracts of land not far from the Kuchar home were being cleared to make way for the construction of the infamous Cross Bronx Expressway. Debris-strewn blocks of abandoned buildings waiting for the wrecker’s ball provided illegal recreation for George, who delighted in pushing rusty refrigerators out of top floor fire exits to watch them explode in the rubble below.

George’s own neighbors were being pushed out of upper-story windows on the pages of his actively cluttered drawing pads where he developed a comic-book drawing style, and later, a style of painting that might be called “Vulgar Humanism au naturel.” Mike also displayed drawing talent at a young age, and likewise eventually took up the painter’s brush to create a series of pictures in the vein of “Mystic-Classical.” (Mike’s apex as a painter came with a series of compelling oil portraits that evoke a satanic eroticism at once evil and pleasurable, with muscular, leering jinns rendered in glowing bright colors.)

Mom was a housewife and Dad, as George describes him, “was a virile, sex-crazed truck driver who slept all day semi-nude, and lusted after booze, bosoms, and bazookas (having served in the Second World War).”

His dad’s taste in literature and cinema would have a profound effect on George, as he recalls in a 1989 interview: “In New York there were a lot of trashy novels on the bookstands, and my father was into reading trashy novels, or at least novels that were exciting to me – the artwork on the covers. That inspired a lot of imagery in my head. I loved the kind of sordidness of what it was like, evidently, to be grown up. It was a turn-on for me, I’d get excited looking at those paperback covers. And also the comic books. I think they twisted me also. I remember I used to be real disturbed when the heroes were captured, and whipped … and beaten, and …

“My dad also used to belong to a little film exchange group, he used to bring home the ‘red reels’ – red plastic reels of 8mm pornography. He had some pornographic books stuck away in his drawer, too, and when I was a little kid I used to find them, and look, and was amazed and would laugh … these adults. The world of adults.”

George’s later literary reminiscences of a Bronx childhood would throb with the same lurid glow that characterized his films. In an excerpt from a 1989 essay titled “Schooling,” George relates: “Going to elementary school in the Bronx was a series of humiliations which featured Wagnerian women in an endless chorus of: ‘Keep your mouth shut,’ ‘Where’s your homework?’, and ‘Spit that gum out!’ The male teachers were much shorter than the females and whatever masculine apparatus they possessed was well concealed amid the folds of oversized trousers. After school my twin brother and I would escape to the cinema, fleeing from our classmates; urban urchins who belched up egg creams and clouds of nicotine. In the safety of the theater we’d sit through hour upon hour of Indian squaws being eaten alive by fire ants, debauched pagans coughing up blood as the temples of God crashed down on their intestines, and naked monstrosities made from rubber lumbering out of radiation-poisoned waters to claw the flesh off women who had just lost their virginity.

“When three hours were up we would leave the theater refreshed and elated, having seen a world molded by adults, a world we would eventually mature into. At home, supper simmered on the stove, smoking, bubbling, and making plopping sounds as blisters of nutritious gruel burst just like the volcanic lava in those motion pictures. Oh how I wanted to grow up real fast and be one of the adults who sacrificed half-naked natives to Krakatoa or dripped hot wax on a nude body that resembled Marie Antoinette.”

The brothers virtually lived in the theaters, seeing everything that came out, seeing the same movies over and over (“We saw Douglas Sirk’s Written on the Wind something like 11 times when it first came out,” says George) … rolling under the seats, climbing through the balconies, making games.

The brothers’ introduction to hands-on filmmaking came courtesy of an aunt who let them loose in a closet full of her 8mm vacation reels which they would watch and edit in sequences that followed their own logic.

For their 12th birthdays, they were given an 8mm DeJur movie camera. They immediately began to stage productions inspired by the epics they saw on the big screen. In a 1964 interview with critic Jonas Mekas, George describes one of these first films. “At the age of 12 I made a transvestite movie on the roof and was brutally beaten by my mother for having disgraced her and also for soiling her nightgown. She didn’t realize how hard it is for a 12-year-old director to get real girls in his movies. But that unfortunate incident did not end our big costume epics. One month later Mike and I filmed an Egyptian spectacle on the same roof with all the television antennas resembling a cast of skinny thousands. Our career in films had begun.”

In a 1993 interview, Mike reflects on these earliest productions: “I forget what is actually the first one. Some of them we threw away. We did one, The Wet Destruction of the Atlantic Empire (1954) [often cited as the first. -Ed.], which had a flood at the end. We did matte paintings of the city and we stuck it in a fast-running stream and ran the camera in slow motion and it was like a flood. We had some friends dressed up in costumes which were really bed sheets.”

These first films were largely improvised. Screwball (1957) was envisioned as one continuous love scene, but that got boring so they had the hero go insane and strangle the leading lady. The Thief and the Stripper (1959) typified a lasting Kucharian penchant for peddle-to-the-floor melodrama: an artist murders his wife after falling in love with a stripper, while the stripper falls in love with a burglar. All die violently as it turns out that the stripper is actually the sister of the murdered wife.

Meanwhile, “real life” occasionally intruded on the brothers’ activities. In an excerpt from the essay “Schooling,” George remembers his teenage years and the emergency brake his Catholic upbringing tried to apply to his sex drive: “Eventually I had to leave the Church as one warm, lonely afternoon I found myself kneeling in a pew praying for wild, disgusting sex. I was a teenager with a heavy inclination to explore my own groin, and the emissions threatened to put out the fire in the sacred heart of our Lord. I looked around me at the elderly ladies scattered here and there throughout the shadowed house of God and knew that they at least were in peace because they didn’t possess a big piece that defiantly poked holes in Christian dogma, demanding lubricated shortcuts to the Kingdom of Heaven. I fled from that place of holiness that warm, lonely afternoon and God answered my prayers: a young, suffering Christian was granted wild, disgusting sex. Praise be the Lord!”

Mike and George were both enrolled at the Manhattan School of Art and Design, which specialized in training for commercial art. Mike, who matured faster than George, eventually got his own apartment and adopted a “swinging lifestyle,” as George terms it.

If George’s teenage years in the Bronx were the essence of adolescent desperation, he did find an emotional outlet in making movies. “I was social making movies. It was my one connection with other people. I used to show my pictures at friends’ houses, at parties. I’d go to the house of friends, they’d be in the cast and I’d shoot the film. A week later we’d come back with the film developed and show them the rushes and shoot more, then maybe a week after that I’d edit it all together and we’d have a party and show the finished film.”

Many of these film parties were held over in Queens, at the house of a high school classmate who would later become their best-known “movie star”: Donna Kerness. A dancer and aspiring model, Donna had a way of moving and expressing herself. She had an indefinable resonance onscreen, but also other more definable attributes: “She had big bazooms,” recalls George, “and she had a very nice face. She could act.She had a style about her. So I put her in movies. All my Bronx buddies were excited about her – they thought her a great sensation. So I milked her: I went over to her house and we began to put her in bathtub scenes, where she wore a bathing suit, of course – the straps were pulled down. We simulated the tawdry stuff that I used to see on the big screen.”

Some of the topical scandals and phobias of the day found expression in the brothers’ films. Their film Night of the Bomb, for example, plays as an 8mm take on the Cuban Missile Crisis that ends in an all-destroying explosion. “When the bomb was supposed to go off, all we did was put chairs on top of the actors as if they were debris – we tried to tangle them up in chairs,” Mike says.

Such violent, apocalyptic endings were common to most of their early 8mm films, for example the all-consuming fire at the end of Pussy on a Hot Tin Roof (1961). “All those movies end in fire,” recalls George, “horror pictures … the house collapses. We tried to make big spectacular endings.”

“The bomb in Night of the Bomb,” adds Mike, “was a vehicle to use as a spectacular image – people in conflict – otherwise it’s hard to make a narrative if something dramatic doesn’t happen.”

The brothers scored these 8mm films with soundtracks laid down on reel-to-reel tapes that ran in loose sync. The music they chose reflected their love of ’50s big screen composers like Bernard Herrmann, Franz Waxman, and Alex North, but all sorts of other audio oddities ended up mulched into their soundtracks, oddball cuts pillaged from a vast record collection they began amassing in their early teens which is still a resource in scoring productions.

The tape soundtracks to some of these earliest films have badly degraded. “It’s been many years,” says Mike, “they’re like mummies now.” George recently began transferring some of these 8mm films onto video in San Francisco. The original and sometimes defective soundtrack tapes were in the Bronx in his mom’s closet (along with the original prints), so he ended up composing new soundtracks for Pussy on a Hot Tin Roof and Tootsies in Autumn(1963).

These 8mm productions (1954-1963) percolate with the influences of just about everything that hit the screen during this period. Of the Hollywood directors, Douglas Sirk was a major inspiration, along with Otto Preminger, Howard Hawks, and Frank Tashlin, to name but a few. Special effects artists like Ray Harryhausen and Willis O’Brien also had a big impact. But just as important, if not more so, were the B and Z grade horror and sci-fi films of directors like Roger Corman, Albert Zugsmith, and Jack Arnold. Studios like Allied Artists, Astor, and especially American International Pictures (AIP) were key to this exploitation boom that would reach a peak in 1957–58. AIP alone released 42 pictures over this two-year period, including titles like Voodoo Woman, The Astounding She Monster, Attack of the Puppet People, and The Screaming Skull.Mike and George saw most of them as their gray matter grew as polluted as the nearby Harlem River.

The brothers’ first public screenings took place at the 8mm Motion Picture Club, which met regularly in the function room of a Manhattan hotel. “It was run by fuddy-duddies,” George recalls. “Everybody got dressed up and they showed their vacation footage. There’d be old ladies, and the old ladies would be sitting next to old men, and their stomachs would be acting up and making noises. And the old ladies would get offended at my movies because they were ‘irreverent,’ I guess. I was looking for … subject matter … and I’d pick anything out of the newspaper. That was after the Thalidomide scare came out and ladies were giving birth to deformed babies, and I made a comedy out of that (A Woman Distressed, 1962) – that was the last time I was at the 8mm Motion Picture Club, and it was the only time they ever gave a bad review to a movie.”

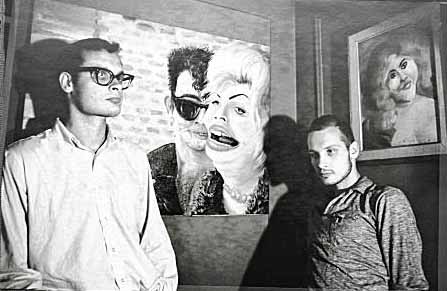

The early ’60s would witness the emergence of the underground film movement (aka “New American Cinema”) on New York’s Lower East Side, centered around venues like the Charles, the Bleecker Street, and the Gramercy Arts theaters. For a while in 1963, informal screenings were also held at filmmaker Ken Jacobs’ Ferry Street loft located downtown between the Fulton Fish Market and the Brooklyn Bridge. At the suggestion of filmmaker Bob Cowan, an actor in the brothers’ movies whom Donna Kerness had brought into the scene, Mike and George took I Was a Teenage Rumpot (1960) and some of their other films down to Jacobs’ loft. That was the night the Underground met the Kuchar brothers.

The fey, decadent milieu of the Underground, populated by dilettantes, beatnik intellectuals, and gay artistes was spiritually a million miles away from the workaday tenement neighborhoods of the Bronx – not to mention well over an hour distant by subway. This first encounter was one of mutual incomprehension. As George recalls, “There were all these underground people. We came in suits and we showed these 8mm movies, and I guess I was kind of a bit square-looking but the movies took off. I wasn’t always liked at that time, I know, because I guess I appeared kind of snotty sometimes to those people. I was just … callously irrelevant, maybe? But they were kind of snotty, too, some of those people.” (In an article on experimental cinema in the April 1967 issue of Playboy, authors Knight and Albert wrote, “The Kuchars take neither themselves nor their movies too seriously. For the most part the Underground is a dreadfully intense bunch of people.”)

Jacobs, also a tireless promoter and programmer of underground film, liked the movies and put them on the “circuit” – whenever there was an 8mm show, the Kuchar brothers were usually on the bill. Mentor and critic Jonas Mekas began to write regularly about them in theVillage Voice and Film Culture magazine. Mike and George were now officially part of the Underground, a rising movement that had ideas, energy, and a following of righteous supporters. Perhaps most importantly, because so many of the films flaunted an in-your-face sexuality, the movement attracted publicity and created an audience far beyond its original borders.

The brothers were now exposed to a whole new world of independent filmmaking which they would influence and in turn be influenced by. They saw the films of Andy Warhol, Stan Brakhage, Kenneth Anger, and others. “I met Warhol a few times,” recalls Mike. “‘Hello, how are ya?’, and I used to see him coming out of my shows. I would go to see his shows and sometimes he would bring his films into the booth where I’d be, ’cause at the time some of the projectionists were my friends – he had to give directions to the projectionists. And Kenneth Anger, we saw Scorpio Rising when it first came out … met him a couple times. It was like ‘Oh – we finally meet!’ – ’cause we’d heard of him and he’d heard of us.”

“That was kind of an exciting period,” says George. “One foot in the lobby, one foot in the street. The street was full of people in business suits, and they’d be coming in, and there’d be more … bohemians inside. A mixture.”

The early 8mm films were shot on old Kodachrome stock that tended to bleach out, but by 1963 Kodak had changed their 8mm stock to Kodachrome-2, which gave a richer, finer image, and the brothers took advantage of it for one of their more lurid plots in Lust for Ecstasy, which premiered at New York’s New Bowery Theater (later named the Bridge) in the early spring of 1964.

“Lust for Ecstasy is my most ambitious attempt since my last film,” George said to Jonas Mekas at the time. “The actors didn’t know what was going on. I wrote many of the pungent scenes on the D train, and then when I arrived on the set I ripped them up and let my emotional whims make chopped meat out of the performances and story. It’s more fun that way and then the story advances without any control until you’ve created a Frankenstein that destroys any subconscious barriers you’ve erected to protect yourself and your dime-store integrity. Yes, Lust for Ecstasy is my subconscious, my own naked lusts that sweep across the screen in 8mm and color with full fidelity sound.”

The brothers playfully satirized the underground in their final production of 1963, Lovers of Eternity, an overcooked ode to bohemian decadence and artistic angst on the Lower East Side. The film starred several noted underground filmmakers, including Jack Smith and his neighbor Dov Lederberg. Lederberg was notorious for cooking his 8mm film in the oven until it assumed the texture of eggplant and then projecting it.

Lovers of Eternity was also the last 8mm film the brothers would make before switching to the 16mm format in response to the better detail and clarity they saw that other filmmakers were getting in that format, and the fact that you could put the sound right on the film. Ironically they had inspired other filmmakers to switch from 16mm down to 8mm (Super-8 wouldn’t arrive until the early ’70s). 8mm became more “underground” to filmmakers seeking the ultimate in a personal, anti-commercial form of expression. The home movie was suddenly cool, prompting from the more verbose members of the movement – Mike and George included – satirically pompous manifestos on the revolutionary purity of 8mm film. (Jack Smith changed from 16mm to 8mm, too – but only because his 16mm equipment had been stolen.)

The brothers began work on their first 16mm production, a black-and-white noir action drama called Corruption of the Damned (1965). Mike starred, garbed in a trench coat and embroiled in long chase sequences. A marvelously filmed brawl in a flour factory recalls the plaster warehouse punch-up in Kubrick’s 1955 noir Killer’s Kiss.(The Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley recently undertookCorruption as a preservation project, assembling a compilation print from which they struck a new negative, salvaging the film for posterity.)

With their jump to 16mm, the brothers developed individual, if similar, styles, and would eventually go their separate ways – although they continued to assist on each other’s productions when needed. Corruption of the Damned began in the usual collaborative fashion of the 8mm films, but Mike abandoned it mid-production to embark on a color science fiction film, and George finished it. “That movie is 80% George’s,” Mike estimates.

The color science fiction film, financed by paychecks from Mike’s day job as a photo retoucher, was Sins of the Fleshapoids (1965). Sins would stand as Mike’s best-known film and the single most significant, creatively realized example of ’60s camp cinema sensibility. Pulsating with excessive colors, Sins unfolds while the camera’s eye floats indulgently over bright flowing fabrics, jewelry, tropical plastic foliage, and platters of glowing fruit that evoke a corrupt paradise.

“My specific aim was to bombard and engulf the screen with vivid and voluptuous colors,” said Mike of Sins in a 1967 Film Culture interview, “because Sins is a fantasy of science fiction. So I tried to boost the colors according to its category: ‘fantastic’ or ‘unreal.’ I intentionally used a color film that when reproduced in the final print becomes ‘unnatural’ and ‘souped up,’ especially in the reds.”

Sins starred Gina Zuckerman, Maren Thomas, Donna Kerness, and Julius Middleman (who later became a cop). Bob Cowan, who narrated the film and chose the music, gives a jerky, deadpan performance as the lead male robot, and George steals the show as Gianbeano, evil prince from the future.

The story transpires a million years in the future, after “The Great War” has depopulated the earth and ravaged the landscape. Mankind, reduced to a debauched few, has forsaken science for greedy indulgence in all the carnal pleasures afforded by art, aesthetics, and lust, leaving work to be done by a race of enslaved robots. One rebellious male robot (Cowan) tires of pampering his lazy masters and murders a human woman after a failed rape attempt, then engages in successful robot sex – the touch of fingers – with a female android. Thus the Fleshapoids join their human masters in sin … and in procreation, as the female android gives birth to a baby robot.

Although Sins is set in the future, there is a classical look to the costuming and set designs that foreshadows Mike’s fondness for an ancient, muscular, Roman sexuality that he would elaborate on in later films and in his published gay pornographic comics.

Sins of the Fleshapoids played midnights for three weeks at an established theater in Greenwich Village and went on to become a staple of the underground. Mike was now able to quit his day job and live for six years off the income of his films, which included, among other things, sales of prints to museum archives worldwide and honorariums for presenting his work at university and film society screenings. (This was more a testament to Mike’s modest expenses than to any vast sums generated by the films.)

Along with Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1964) and Warhol’s The Chelsea Girls (1966), Sins of the Fleshapoids remains one of the three most influential works of the ’60s American Underground, if one of the least self-consciously scandalous. It was never busted like Scorpio Rising (for a snippet of frontal male nudity), nor did it have the aura of fashionable decadence that radiated from everything Warhol attached his name to and that propelledChelsea Girls to heights of fame and financial success arguably greater than the film’s value. (At a sold-out 1991 screening of Warhol’s film in Boston, the entire audience left during the unannounced intermission.) That Sins achieved the influence and success it did without sexual scandal or the scenester celebrity that many other underground films exploited is notable.

Subway Auteur: The Sound and the Fury Signifying Something

Fresh from his performance in Sins and with Corruption behind him, George launched his first 16mm color production, Hold Me While I’m Naked (1966), a 10-minute piece that would become his signature film. An abstract meditation on the emotional and technical traumas of making a low-budget movie, Hold Me was a deft parody of Hollywood stylization. With its aura of personal frustration and loneliness it was also a direct read of George’s then-current mental state. In fact, while this and other of George’s mid-to-late-’60s films invariably provoke laughter from audiences, George never considered them comedies.

In 1988, he reflected on the paradox: “My movies were playing in New York City once, and this woman I know said ‘Let’s go to your show – they’re having a night of your movies at the Film Forum.’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t want to because I don’t want to relive all the pain.’ I realized my career has all been based on pain. Those movies, even the funniest ones, had this horrible pain behind them. And I know exactly why they were made. I didn’t want to go because I didn’t want to relive that – I didn’t want to relive the main motivations of those pictures. (But then I went and there were people laughing, and I was even laughing, having a good time. And I forgot about the pain.)”

At this point, George was financing his films with “paychecks from hell” that he earned as a messenger for Norcross Greeting Cards in Manhattan. George recalls the place was run mostly by women. They were “amazons … large, frightening, terrifying amazons that walked the halls all made up and smelling of perfume. Madison Avenue type women, clacking down the halls. Frightening, terrifying figures. I don’t know what was wrong with those women, but … I do know what was wrong with those women, they had ulcers, some of them were eaten up alive … they were like men with wigs on. And in fact some of them looked like Glen Strange, the Frankenstein monster. Their faces were horrid …”

After Norcross, George got a job as a chart illustrationist for NBC’s weather show. His daily subway commutes to Manhattan sparked his writing, which resembled the style and vocabulary of his cinema as revealed in an excerpt from his 1988 essay “Early Role Models”:

“It was thrilling to ride the jam-packed subway trains to work in the morning: discreet perverts would reach out for some sort of stabilizing support so as not to lurch over and fall in the rocking cars and they’d grab onto your private appendages. Full-figured senoritas would mash you against metal partitions using flesh of such abundance that no amount of latex rubber could suppress the meat into trim decency. Fights would suddenly break out with alarming ferocity but there could be no room for swinging fists and so the squeeze of the traveling mob would suffer further, violent escalations. In those subway train cars the hot, metallic-smelling air was supercharged with the most primitive of living emotions. We would all spill out of these cars (some of us being pushed or thrown out) and climb the stairs into the canyons of dark glass and gargoyled stone which housed the machinery of commerce and coffee breaks, industry and indigestion, finance and fiscal flatulence that smelled of syndicated corruption.”

The 1966–67 period was a busy time for the brothers as they honed their individual styles and saw their films go into wider distribution, due to the continuing momentum of the Underground.

Of the three films George made in 1967, Eclipse of the Sun Virgin was probably the stand-out. Starring Larry and Francis Leibowitz, Eclipse was similar in pacing, length, and style to Hold Me While I’m Naked, but throws up more extreme imagery and ends with George and Larry watching found tracheotomy footage on George’s projector. On the surface it plays as a colorful, bawdy burlesque of life, love, and supper in the Bronx, with George caught between the many-headed hydra of lust and the bony grip of Catholic guilt.

John Waters’ oft-repeated statements that “Beauty is looks you can never forget” and that “A face should jolt, not soothe” were ideas George was already drawing on in Eclipse where he pays sincere homage to rotund Bronx babes and facially imperfect others.

Movies of the Moment: True Underground

Mike followed Sins of the Fleshapoids with The Secret of Wendel Samson (1966), casting famous avant-garde artist Red Grooms in the lead role. Secret is a personal story told in the vocabulary of expressionism and pop fantasy. Entrancing use of dreamlike musical collage merges with fluid hand-held camerawork to express the inner turmoil of Wendel, who is caught between his diminishing sexual interest in a current girlfriend and unfulfilling gay relationships. Set largely in a series of spare interiors and on a desolate, snowy plain – in contrast to the lavish sets and atmospherics of Sins – Secret is a surreal, troubled rumination on sexual need and the entanglements of relationships. It remains one of the most uniquely personal and overlooked works of the ’60s underground.

The Secret of Wendel Samson illustrates Mike’s philosophy that a film is the unchartable confluence of personal inspiration and all-important “chemistry” – a creation of the moment unrelated to what had come before or would come after.

In a 1988 interview, Mike reflects on his approach to filmmaking: “I can only do a film when I feel really inspired or when I really want to. What mood I’m in determines what I’m going to do. For every film, if the chemistry is just right, then I’m able to make it. It’s very hard to make a film like Sins of the Fleshapoids again because I don’t fall back into that chemistry – where everything comes together. You meet these kinds of people and they’re just right to fill the parts for this film that you’ve always had in mind. I have a few films that I want to do, and they’re not really related to each other, but then I’ll make them when I meet the right people or discover the right place to film it in. It’s a matter of chemistry. Then it works and stands on its own, unto itself. Then life goes on … until something else brings out something that you’ve always wanted to make. You know when it’s right and then you go out and buy the film and make it.”

Mike’s straightforward approach to filmmaking, obviously antithetical to commercial cinema or the “careerism” seemingly endemic to every form of human endeavor today, encapsulates the transitory nature of true underground. His refusal to work within an identifiable genre and produce films synonymous with audience expectations, or films that are predictable or “characteristic,” precluded his achievement of the fame of many of his contemporaries, including George. This is also why he is one of the very few pure underground filmmakers.

In its truest sense, “underground” was not a genre but an anti-genre. Underground was an image-negative term that refuted, denied, and disowned definition rather than encouraged it. A thing underground was a thing unseen, something ominously “other” happening in the darkness. The underground film movement was never more than a collection of individuals who never quite collected. As with any creative cultural movement with claims to revolutionary purity, it was threatened most by its own success – the blacklisting of venues, censorship, and police harassment pale by comparison. Popularity breeds pressure. Public demands for follow-ups and remakes from the often more-than-happy-to-oblige stars of the movement suck it dry of any spark or spontaneity as it ossifies into paid entertainment, and the movement rolls over and dies in a cloud of financial squabbling and superficial notoriety. In a milieu rife with spotlight-hogging enfant terribles, prima donnas, and media-savvy mythmakers, Mike never “followed up” and never sought celebrity – he just made his movies.

In Hold Me While I’m Naked, George framed certain scenes by turning the camera on his own face from low or straight-on angles, putting his personal stamp on a shot that might be called “house- of-mirrors close-up.” Used occasionally in his ’60s 16mm shorts, George emerges via these intimate portraits as something of a graceless, overgrown goofus with mild acne and hair that “sticks up like a toilet brush,” as he describes it.

There were other sides to George, however, and a radically different persona is captured in Michael Zuckerman’s lost 12-minute nugget from the psychedelic underground, Soul Trip Number Nine (1969). As Zuckerman describes it, Soul Trip is “a story of burned out love … taking the viewer to the shadow world of dreams and yearnings that hover in the psychedelic twilight of the turned-on mind. Slowly, as the lovers sink deeper into a drugged state, their unconscious desires rise to the surface. In brilliant colors the images tumble across the screen to reveal the feelings evoked by this, their last trip together.” George, smoothly done over in pancake make-up, a Beatles wig, and mod clothing, cuts an effectively dashing and soulful figure as leading man in his nonspeaking role. A bevy of topless young women cluster and swirl around him in kaleidoscopic fashion via masterful superimpositions and other hallucinatory effects.

Portrait of Ramona (1971) signaled a major turning point in his life and filmmaking. George recalls this, his last New York film, in an interview from January 1989.

“At that time Mike was friends with this deaf guy. He could speak fairly well but he knew this other guy who was also deaf, I think from birth, and he learned how to talk just by watching people’s mouths open or something. Listening to him speak was the most amazing thing, you couldn’t really understand it but it was an interesting combination of sounds. And I wanted him to narrate Portrait of Ramona. But some of my friends looked at me with shock, like, ‘How could you do such a thing?!!’ I actually thought it would be interesting to hear his voice on the soundtrack. It wouldn’t matter if the audience understood it or not because they would be hearing a narrator and they would know the thing is somehow being explained, even though they didn’t understand it, and so they’d accept the visual format of the film better.

George unfailingly refers to Portrait of Ramona as a “desperate scream for help.” It was time to move on to new things, to start a new chapter – to get the fuck out.

It was time to leave the Bronx.

In 1971 George attended a film festival in Cincinnati where he made the acquaintance of fellow filmmaker Larry Jordon, who was (and still is) teaching film at the San Francisco Art Institute. Jordon began in film as a compatriot and disciple of Stan Brakhage but would himself become a major figure in the underground for works that spanned a remarkably wide range of styles. He would become best known for a series of animated collages, most notably Duo Concertantes (1962–64).

Larry asked George if he wanted to teach film at the San Francisco Art Institute (S.A.I.) as a visiting artist for a one-year period. George accepted the offer and packed his bags. He moved out to San Francisco and never left.

George remembers his first student on that opening day of school. The young man had actually beaten him to class and was sitting on a desk in cut-off jeans and sandals, swinging his feet, when George walked into the room that morning at 8:45. From first impressions, this bearded, sandy-haired kid seemed “like a nice, playful person.”

The punctual student was Curt McDowell, and sitting on a desk in film class was one of the lesser dictates of cinema he would go on to break.

Born and raised in Indiana, Curt never lost his Midwest mannerisms. “He was a pumpkin-pie type of person,” George recalls. “You know, cooking food, being social, a real Indiana transplant, sewing costumes and telling us stories about his mother … he was also a catalyst; he brought people together and got them involved in situations they normally wouldn’t have gotten involved in, sexual and otherwise. Well … like, I never cared for bowling, but when you went out bowling with Curt it was fun. But he was also this kind of lewd, crazy person who went on binges.”

Enrolled at the San Francisco Art Institute in the late ‘60s on a painting scholarship, Curt was turned on to movies by instructor Bob Nelson and switched to the film department. “And so,” George remembers, “we began to share each other, first literally then on the screen. He would use me in his pictures, in musicals and stuff like that – which gave me an opportunity to sing even though I can’t hold a note.”

Curt circulated a petition to get George hired on a permanent basis, arguing that the school needed new blood from outside, new influences. George was hired. Mike also began to spend time in San Francisco.

Starting out as a protégé of George’s, Curt quickly found his own style and began to incorporate a large circle of friends, artistic collaborators, and virtual strangers off the street into the more than 30 films he would make. “He made friends everywhere,” recalled companion and lover Robert Evans in 1987, “and he eventually talked most of them into taking their clothes off and appearing in his movies.” A host of his friends, including George, Mike, and his own sister Melinda, were featured in his poetic 1975 film Nudes: A Sketchbook.A stylistic departure from the grainy, rough-hewn pornographic look Curt often favored,Nudes is a gentle homage to the sensuousness and physicality of those close to him.

From the outset George would find San Francisco planets apart from the Bronx, especially when it came to the libido. “The City was considered an outdoor bordello at that particular time,” he muses today as if looking back at another century. Indeed, San Francisco in the early ’70s was capital of the booming hardcore porno industry which native sons Alex DeRenzy and Jim and Artie Mitchell had pioneered in 1969, and the gay underground was pulsing with energy. A not-yet-famous Divine could be found holding court down at the Palace Theatre in North Beach, starring in stage productions like Vice Palace and Divine and Her Stimulating Studs, while across town the Castro was beginning to coalesce into a major gay enclave. In the Mission district, a dank, narrow 200-seat theatre showed non-stop porno flicks. (In 1976 Robert Evans took over this theater, the Roxie, and turned it into one of the most important indie rep venues in the country, still going strong today.) A hothouse atmosphere saturated the City, and the Art Institute served as a clearinghouse for the out-of-control libidos of the artistically inclined.

McDowell was not the only Art Institute student bent on exploring the limits of erotic cinema. In a 1988 essay called “California Concoctions,” George describes a typical student film of the period and the effect that all of this was having on him:

“Young people in the City by the Bay were aiming their movie cameras at exposed chakras left and right as the Sexual Revolution was in full swing at that time. One female in my class was up on the silver screen being sodomized by a latex novelty while indulging in a coke of non-carbonated powder. The person on the other end of that rubberized intrusion was a female classmate of lesbian persuasion obeying the direction of a unisexed university urchin who looked like Hermaphroditos incarnated … Eventually I fell victim (happily) to this quagmire of humping and heaving viscosity and embarked on an orgy of flesh-debased delinquency that knew no bounds…”

Meanwhile Mike would continue back east through the ’70s with a slew of his own films:Aqua Circus (1971), Digeridoo (1972), Faraway Places (1972), Death Quest of the Ju-Ju Cults(1976), and Dwarf Star (1977) among them.

Factory of Desire: The Low-Budget Ecstasy of the Class Films

George’s own filmmaking now took two distinct directions: the class films he supervised at S.A.I., and his own personal films.

The class films were cast and crewed with the students who took George’s course, many of whom had specifically enrolled at S.A.I. to study film with him, some coming from Europe and Latin America. These class films tested George’s resourcefulness since he was confronted on the first day with up to 30 students, each of whom had to be involved in some way, some speaking limited English.

Facing a linguistic gridlock that would give other instructors an ulcer, George leaned into it with gusto and actually sought out students with pidgin-English-speaking abilities for starring roles. “In those days,” he recalls, “James Broughton was teaching at the school, and always complaining. He had a screenwriting course and he was always complaining that the class was full of foreigners who could barely talk English, much less write it. And I was always sayin’, ‘Well, send them to me!’, because I loved those accents – they gave the pictures a continental flavor. They had strange pronunciations of words and they made the screenplays come alive in weird ways.”

The budgets were always small for these class films and George’s talent for spontaneous improvisation was constantly tested, distilling the productions down to the essence of low-budget filmmaking. He often wrote the dialogue and scripts on the spot, locked in a nearby closet so he could concentrate. Once, lacking dialogue for an actress, he told her to recite Shakespeare. She did. It worked.

George’s approach to directing a student cast was to create custom-tailored scenes and roles that would best exploit the multifaceted talents and looks before him, playing to individual strengths and enthusiasms, freeing the energy rather than subjugating it within the disciplined context of polished scripts, storyboarding, and rehearsals. It was all about chemistry cooked up among the actors themselves and among actors, scene, and setting. It was about spirits, energies, mixtures, and unplanned moments captured.

Instead of trying to compensate for lack of formal structure by coming to class overprepared as many a nervous director might, George turned unpreparedness into an art form and a modus operandi. “In being unprepared you are never sure of what you’re going to do and the sudden chance for discovery and inspiration becomes greater,” he would write. If the productions that resulted bore no resemblance to classical Hollywood narrative film, they did move with a bracing energy and flamboyance. The pacing of the class films would always tend to be uptempo, but from the mid-’80s on they became even more fragmented and episodic as George adjusted to what he believed were the shorter attention spans of the MTV generation. We’s a Team (1989), for example, is a series of vignettes and rapidly executed skits.

Lack of funds also forced him into unheard of technical improvisations. Unhappy with one roll of film that had a kind of orange tint because he lacked the proper lens filter when it was shot, George gave it to a student who soaked it in a plate of bleach. George declared himself happy with the results: she’d fixed the color and also brought in unexpected flashes of lavender into the bargain. Another time, shooting outdoors in sunlight too bright for the film stock – even after cutting down on the aperture – they stuck sunglasses on the lens and it worked. “You could see the two lenses of the sunglasses,” testifies George, “and we positioned each actor so that one would be in the right lens and one would be in the left lens, and they did their scenes. Everything else around them is bleached, but you can seethem well enough through the glasses.”

The constant flow of new students assured that each film would have its own personality, though invariably stamped in the Kuchar mold. Some students would take more than one class and so “stars” would emerge over an “era” of several productions. Sometimes people not enrolled at S.A.I. would drop by and be cast in a film, and George would also cast faculty members, visiting artists, or people wandering by who looked right for a particular role.

The Desperate and the Deep (1975) opens with a striking credit sequence filmed through an aquarium. An enduringly popular film, this talkie drama at sea was designed and photographed in low-budget minimalist style, with everything taking place at night against black backgrounds. The effect of deckside ocean spray in people’s faces was supplied by a student off-camera throwing a dixie cup full of water.

Heated dialogue was needed to fuel these films as well as distract from the scaled-down sets and lack of professional effects. George was always more than equal to the task – sometimes crediting his script to a pseudonym when he deemed the dialog too florid.

One could always count on action in these class films, along with an unhinged exuberance, in contrast with George’s own usually more contemplative, mysterious, or atmospheric personal films. Brawls often erupted in the class films and George himself could occasionally be seen tumbling over cheap furniture and stage sets, as for example in Remember Tomorrow (1979).

Symphony for a Sinner (1979) was a long, lavishly photographed color film generally considered the magnum opus of the class productions. New York critic and coauthor ofMidnight Movies J. Hoberman would rank it as one of the ten best films of the year, while Stan Brakhage would call it “the ultimate class picture.” John Waters, who now visited George regularly whenever he passed through San Francisco, envied the lurid color photography and wanted George to shoot his next picture (which would have been Polyesterand didn’t happen). Symphony, Waters said, had the look he craved for Desperate Living(1977).

Perhaps the real gem of George’s class filmmaking can be found in a forgotten film from the following year, How to Chose a Wife (sic), the concluding third of which features a bizarre wedding chapel scene complete with stumbling, heavily pregnant bride and mystified Arab onlookers. An apocalyptic earthquake erupts – the ground trembles and the chapel walls crumble and crash down in a hallmark scene of mass destruction. George recalls the budget at around $300. Everything was done with inventive camera effects and a keen sense of staging and scoring.

Mike also made a number of class films under the auspices of the San Francisco Art Institute during the ’70s: The Masque of Valhalla (1972), The Wings of Muru (1973),Blood Sucker (1975),The Passions: A Psycho-Drama (1977), Isle of the Sleeping Souls (1979), and in 1984, Circe.

George’s most sustained class film in a narrative sense is probably Summer of No Return(1988). A year and two films later George would start shooting the class films on video due to the rising cost of working in film and his shrinking budgets. It became impossible to conduct a class of 20 to 30 students all semester, all day Fridays, on a budget of $300. Jean Cocteau said that “the cinema will only become an art when its raw materials are as cheap as paper and pencil.” Apparently Kodak wasn’t listening.

The fresh inspiration George found in San Francisco gave his own films a distinct personality from that point on, although his general style would be forever linked to his “Bronx hyper-reality” roots.

Completing The Sunshine Sisters in 1972, George began work on his Gone with the Wind– or what he terms his “white elephant”: the 1973 black-and-white production of The Devil’s Cleavage. Consisting of a series of episodes totaling 21/2 hours, The Devil’s Cleavage was a recreation of ’40s and ’50s black-and-white melodramas that combines heartfelt hommageand deft parody. Curt McDowell excels in the male lead as the putz sheriff spouting bald Kucharian dialogue with a deadpan delivery.

In return for Curt’s help on this film, George assisted Curt on his 1975 feature Thundercrack!This would be their glorious gift to posterity – the world’s only underground porno horror movie. George titled and wrote the film, did the lighting, made up and costumed lead actress Marion Eaton, and acted the role of “Bing,” the psychosexually troubled gorilla keeper who attempts suicide by crashing his circus truck in a thunderstorm. Rumor had it that George wrote the script during a thunderstorm in Nebraska while tripping on LSD. Actually he wrote the 192-page script during a prolonged stay at an Oklahoma YMCA where he used ballpoint pen to preclude erasures and the specter of eternal rewrites.

George wrote the part of Bing, he recalls, “for someone a bit more aesthetic looking – in an Austin, Texas kind of way. I’m sort of bulky but they asked me to do it. Unfortunately I never had time to memorize my lines, which was a great source of embarrassment since I wrote the damn thing! But it seemed to give the character a little edge.” To say the least. George’s performance is one of the most maniacal in the annals of the Underground, ranking alongside his role as Gianbeano in Sins of the Fleshapoids as his most twisted screen appearance.

Sparkles Tavern was Curt’s next feature film and would employ many of the actors from Thundercrack! McDowell wrote the script, George says, while high on LSD in Yosemite National Park. George was cast as “Mr. Pupik” – a mystical stranger with intuitive powers and Dadaist mannerisms who peddles bizarre but effective remedies for personal troubles. George was required to sing, execute arcane dance steps, and play the saxophone (actually the “air saxophone”). Shot in 1976, Sparkles was not edited and released until 1984. Three years later, on June 3, 1987, Curt McDowell died of AIDS at 42. (The original negatives of both Thundercrack! andSparkles Tavern have since been lost or destroyed, apparently due to oversights by the Curt McDowell Foundation.)

George’s 1979 film Blips would initiate a six-part UFO series inspired by UFOs he was spotting at the time. In a 1988 interview, he says, “In the mid-’70s I found out that UFOs are real. Whatever they are – I don’t know what they are. But there was a big rash of them and they were in California, in San Francisco. I happened to fall into the mess … or mystery, by viewing what were UFOs. They were of different colors and they came in a series that lasted about a year and a half. Also in different sizes and shapes … and they have strange mental effects on you. They interact with you in a personal way, although I can’t see how extraterrestrials would have that much interest in you. But from the stories you hear and my own personal experiences, it’s very personalized and bizarre. I began to investigate it in the films.”

Set in several barren, debris-littered rooms, Blips plays as impressionistic soap opera, equal parts Phantom from Outer Space and Waiting for Godot. George was more concerned with portraying the psychic effects UFOs had on people, on their libidos particularly, than with the overworked science-fiction images of UFOS delivering mass destruction. Special effects were minimal.

The UFO sextet continued with The Nocturnal Immaculation (1980), Yolando (1981),Cattle Mutilations (1983), The X-People (1984), and Ascension of the Demonoids (1985), which is George’s last personal film to date.

George received his only funding grant for Ascension of the Demonoids ($20,000 from the NEA), and so, freed from the usual financial restraints, he was determined to have a good time and make a “spectacle” with “tons of color” and dazzling superimpositions and other camera effects. “I wanted to look away from the subject,” George said in a 1988 interview, “so the movie looks away from the subject towards the end. In fact, it completely drops the subject, basically … goes to Hawaii and examines the scenery, forgetting about what had previously happened or what the picture was about. That was my intention. I wanted to get off the subject.”

George gave another inspired performance in the 1984 black-and-white feature Screamplay,an unjustly overlooked ode to silent movie making that featured some astonishing montage and superimposition. Cast against type by Boston-based writer-director Rufus Butler Seder, George plays a dour, reclusive superintendent of a courtyard motel with a convincing sense of menace – a persona in fact recognizable to anyone who has seen George sullenly loping down San Francisco’s Mission Street to the 19th Street flat where he lives today.

These days Mike splits his time between San Francisco, where he shares the flat with George, and New York City, where he works in season at the Millennium Workshop. He periodically tours his films in Europe and the U.S. and works as cinematographer on independent Dutch and German films. In December 1993 he premiered his new video feature film, Purgatory Junction, at the Millennium to a full house. Mike has also given a name and enduring inspiration to the New York City underground-punk band The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, fronted by nude body-painted singer Kembra Phafler and her guitar-playing Japanese husband.

George, with over 60 films and 100 videos now to his credit, has a higher profile. He was the subject of recent retrospectives at The Museum of the Moving Image in Queens and at San Francisco’s palatial Castro Theater, which staged a joint George Kuchar/Curt McDowell retrospective in November 1993. George also continues to teach guest film courses and workshops at universities and film societies around the U.S., but seldom travels abroad. He works almost exclusively in video today.

Since the late ’70s, George has been a regular May visitor to an unremarkable little roadside motel in El Reno, Oklahoma. He’s become friends with the motel’s owner, who now picks him up at the airport. With each visit he produces a “Weather Diaries” video as he kills time in El Reno. He spends his time there filming daily life, clearing his head of psychic flotsam accumulated in San Francisco, and waits for tornados to strike.

The tornados, still …

Has it ever happened?

“When one finally came,” laughs confidante John Waters, “he ran and hid. I’m not sure – he might have been joking.”

– Jack Stevenson